The overall goal of the Art Crayon Toolkit is to increase children’s engagement with art. Specifically, we aim to: (1) encourage children to look closely at the visual elements of art, including color, (2) spark an interest in learning about art and artists, (3) prompt children to actively create and connect art to their own lives.

The intended audience for the Art Crayon Toolkit is children from age 7 to 12. We imagine it would be used in a semi-structured educational setting such as museum workshops, art classes, or after-school programs. Independent use of the Art Crayon Toolkit is a secondary use case.

The intended audience for the Art Crayon Toolkit is children from age 7 to 12. We imagine it would be used in a semi-structured educational setting such as museum workshops, art classes, or after-school programs. Independent use of the Art Crayon Toolkit is a secondary use case.

In order to evaluate the Art Crayon Toolkit, we tested it with three children: two children age 7 and one child age 4 (2 male, 1 female). The four-year-old was taken as a secondary use case, as he was outside the intended age range. We observed the children and ask them questions as they interacted with the Art Crayon Toolkit. We also asked them to talk through their reactions as they worked with the objects in order to get a better idea of their thought process. Finally, we asked a few semi-structured follow-up questions to get an overall idea of their experience. with Art Crayon Toolkit. Example questions include:

– What was your favorite part?

– What part of the workbook did you like?

– Was there anything you’d change to make it easier to play with?

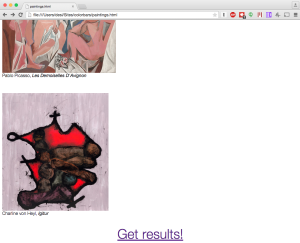

During the testing session, we first asked kids to explore the workbook and crayons on their own for a few minutes. Then, we explained that the art-based crayons were made of many colors corresponding to the hues in a painting or a print. We asked them to match the four art-based crayons in their pack to the four works of art on the first page of their workbook. Kids then picked a particular crayon or artwork and went to the relevant page to learn more about the work of art, examine the bar graph, and do the drawing activity. The first tester was more interested in looking at the works of art and figuring out how the crayon corresponded to it; the second two testers were more excited about the drawing activities.

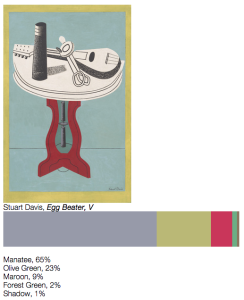

We found that the art crayons were an interesting way to get children to look closely at the works of art, with special attention paid to how the artists use color. Every kid was able to match at least some crayons to bar graph picture, although they found crayons with similar hues difficult to match. The seven-year-old testers reported that they understood the bar graph diagrams in the workbook and how they related to the crayons; the four year old did not understand the correlation. One kid placed the crayon next to the bar graph to line up the colors. In certain cases, very similar colors, such as sepia and brown, were adjacent in the crayon, making it difficult to distinguish between the two (one kid believed that a color was “missing”). Some of the testers read the percentages of different colors in a crayon, showing a basic understanding of how the data in the crayon relates to the images.

While color served as an initial hook to looking at the works of art, some of the kids also noticed elements beyond color. One kid was familiar with Hokusai’s Great Wave print because he had studied Japan in class, but he noted, “I never realized there was a boat right there.” Another tester realized that there is a small skeleton, or calavera, in Kahlo’s painting. The crayons and the content of the workbook served to help kids look more closely at works of art and learn more about the art and artists. Some of the testers read the artist name and artwork titles on the crayon labels, as well as the information about the artworks in the workbook. The thematic groupings were an useful way to spark children’s interest, too; one of the kids reported liking the food theme. As one kid explained, he liked the crayons because it helps him to “know what the artist used to make it. Some art it’s hard to describe what the artist used to make it.”

The Art Crayon Toolkit also encouraged kids to create and connect art to their own lives. Two of the kids were most interested in the drawing activities; they were rapidly pulled towards these activities and later reported these were their favorite part of the entire session. The other tester enjoyed reading the activity and talking about the prompt, but seemed reluctant to color. The kids also were interested in where the crayons came from, asking how we made them. In addition to prompting an interest in artmaking, the Toolkit was a great way for kids to connect art to their everyday lives. One kid has been studying Japan in school; when he saw the Hokusai artwork, he quickly identified Mount Fuji and Kanagawa, the island in the title of the print. The corresponding prompt asked them to think an of ocean scene they’ve experienced, which led him to recount a story about his own time at Martha’s Vineyard. Another kid was familiar with Frida Kahlo and told us about how she had dressed up like the artist for a school event.

While our testers were generally enthusiastic about the Art Crayon Toolkit, they also provided feedback that could help us improve the project in the future. We noticed that the wrappers for the art-based crayons came off almost immediately because the children had trouble seeing the different colors despite the translucent labels. Kids were also interested in using the five colors in each crayon individually. Some of the kids would rub the crayon sideways to reveal the different colors, but others found it frustrating when they couldn’t draw with a color in the middle of the crayon. We found that the structural integrity of the crayons generally held up, but could be improved—a few of the color bar crayons broke when kids drew with more force. The language of the information on works of art could also be simplified for younger audiences; a challenge is balancing art-related words like “pastel” and “depicts” with the reading level of our intended audience. We are also considering changing the supplementary colors in the crayon pack; the kids were not interested in white, and would benefit from having a broader color range.

Overall, our impact study shows that fundamentally the Art Crayon Toolkit is a viable path for increasing art engagement in children ages 7 to 12 and could be further improved by iterating on the design and content.