Val Healy, Nolan Essigmann, Ceri Riley

For reference, here is a link to our final project (we might need to host it somewhere besides c9 for others to view it) and here are our final project presentation slides.

Goals

The ultimate goal of our web scroller is to reveal how humans are exacerbating the social, economic, and environmental impacts of drought because of the current structure of industrial agriculture and government subsidies that reduce the cost of meat and dairy products. We wanted to create a more unique narrative, a story that extends beyond the ‘shock factor’ of revealing water footprint data concerning meat and certain crops.

As such, we introduced the link between drought and the water footprint of foods and debunked the idea that refraining from eating meat – an individual lifestyle choice – will have an effect on the industrial food system and massive daily amounts of agricultural and livestock water use. We wanted to emphasize that:

- lifestyle politics are a good symbolic choice, but not necessarily a practical act of activism (especially if you cannot afford to make the choice due to food costs).

- government subsidies systemically reduce the cost of meat and dairy products, such that their financial cost doesn’t necessarily reflect the environmental cost (the water footprint) that goes into raising the animals

- anyone who wants to be more engaged and enact change should keep updated with information about industrial agriculture water use, government subsidies, and other organizations who are actively trying to reduce wasteful water use in the US

Audience

The audience for our data story is college freshmen, and we gathered the bulk of our feedback from several individuals in our living groups. We selected college freshmen because the demographics of the group vary greatly – people come from different locations, backgrounds, high school education styles, and levels of community/regional/global engagement and awareness. The independence and immersion in a new, open college environment encourages individuals to question their inherent biases and beliefs, and generally incites a desire to be more aware of how they can affect the world in the long run.

As such, college freshmen are an ideal audience with whom we can discuss a popular topic like drought (which they have likely heard of, even vaguely, in the news) and they will be receptive to discussion about how individuals can help (or fail to) influence local water use through their lifestyle choices and activism. Students also may face the dilemma of purchasing cheap, easy-to-prepare food on a budget or may experiment with different diets for health or sociopolitical reasons. In addition, every college freshman presumably has some desire to continue learning, so they may benefit from our educational ‘call-to-action’ and become interested in different organizations that address national water use and/or be more willing to seek out more information on the subject of drought and food.

Reaction

Types of questions we asked:

- Have you heard about drought in the US before this project? What about it?

- What do you think about taking shorter showers (or similar actions) to save water?

- What about changing what foods you eat?

- Did you know that food comprises most of your daily water use?

- What are your feelings towards crop and livestock subsidies?

- Did they change at all after scrolling through this narrative? Why?

- Did you learn anything about drought/do you have any desire to learn more about drought? Or different forms of water use?

- Do you want to get more involved in reducing US water consumption? Your personal water use?

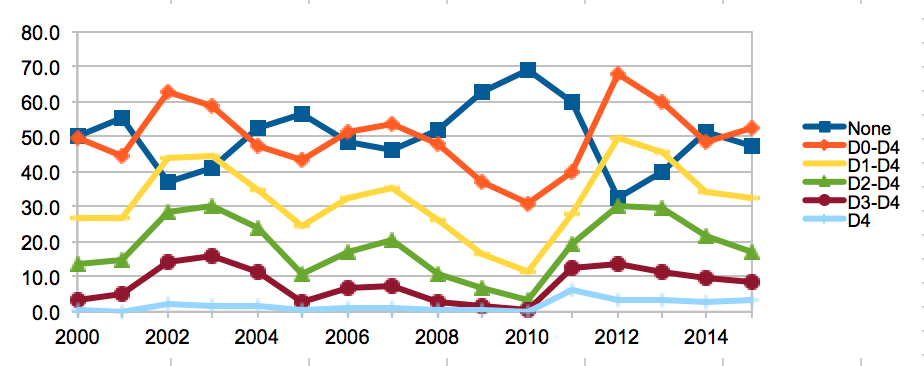

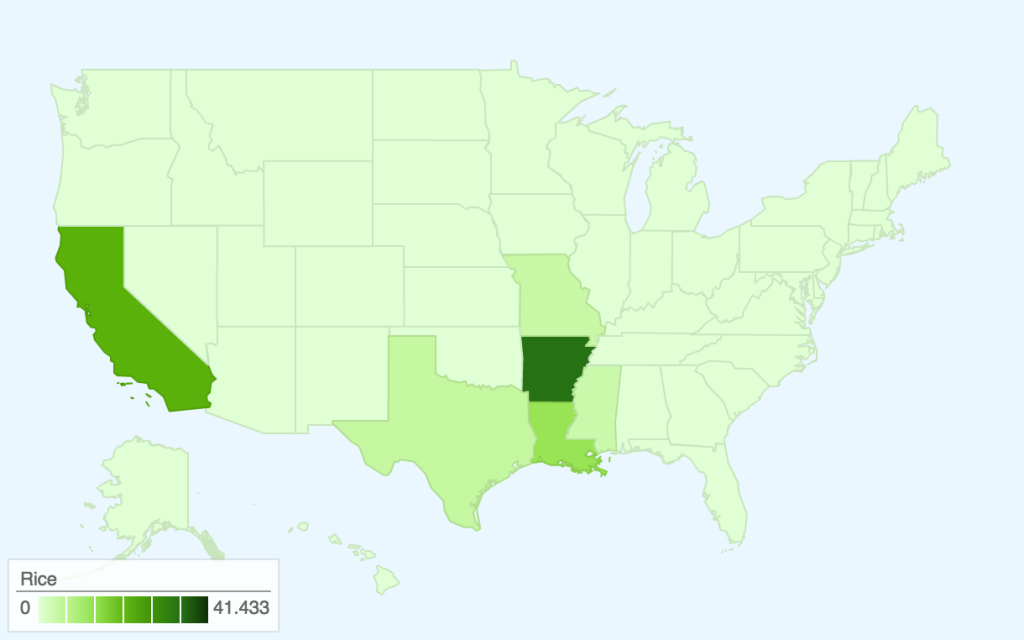

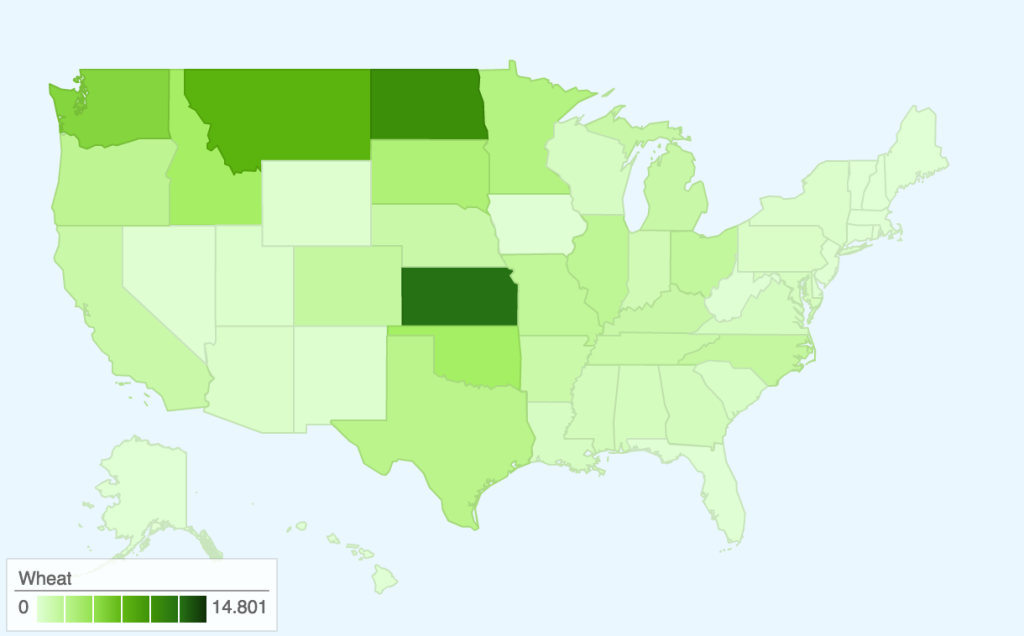

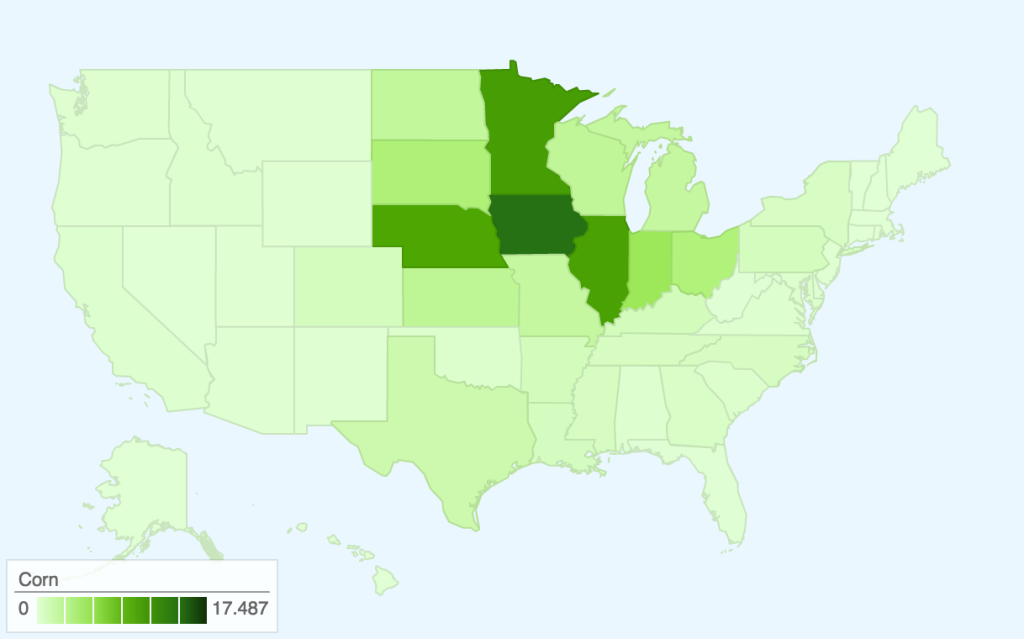

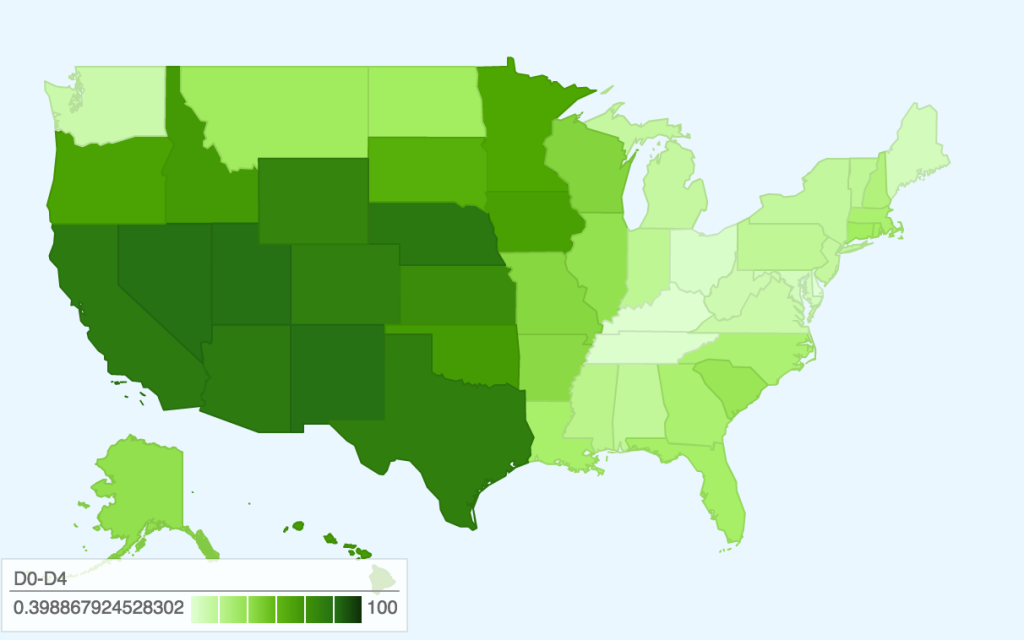

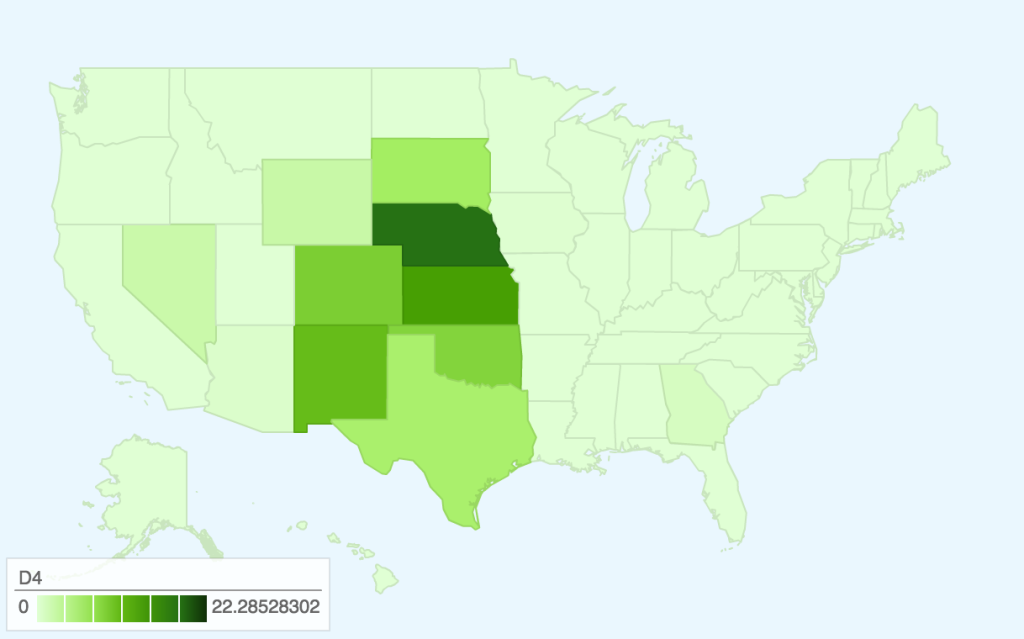

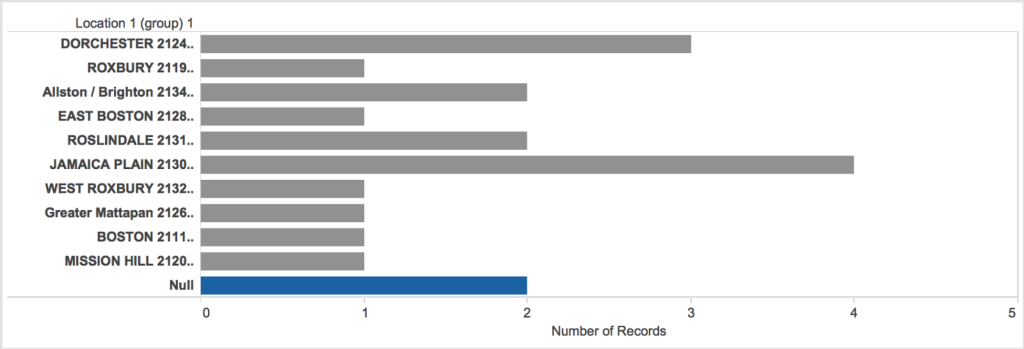

All the freshmen we talked to (approximately 6) had mainly read popular news stories about the California drought, and two of them had grown up in the midwest and heard about the devastating effect of drought on crops. They knew that drought was affecting families, either people they knew who were involved in agriculture or by water bans in California. Overall, there were mixed opinions ranging from “Drought isn’t really a problem where I come from” to “my home county is basically a desert so I’ve pretty much constantly lived in or near drought” to “my grandparents live in California so I probably should know more about it.” They thought the small multiples map was interesting, and were curious about what the different colors/levels of drought actually meant beyond “red = bad.”

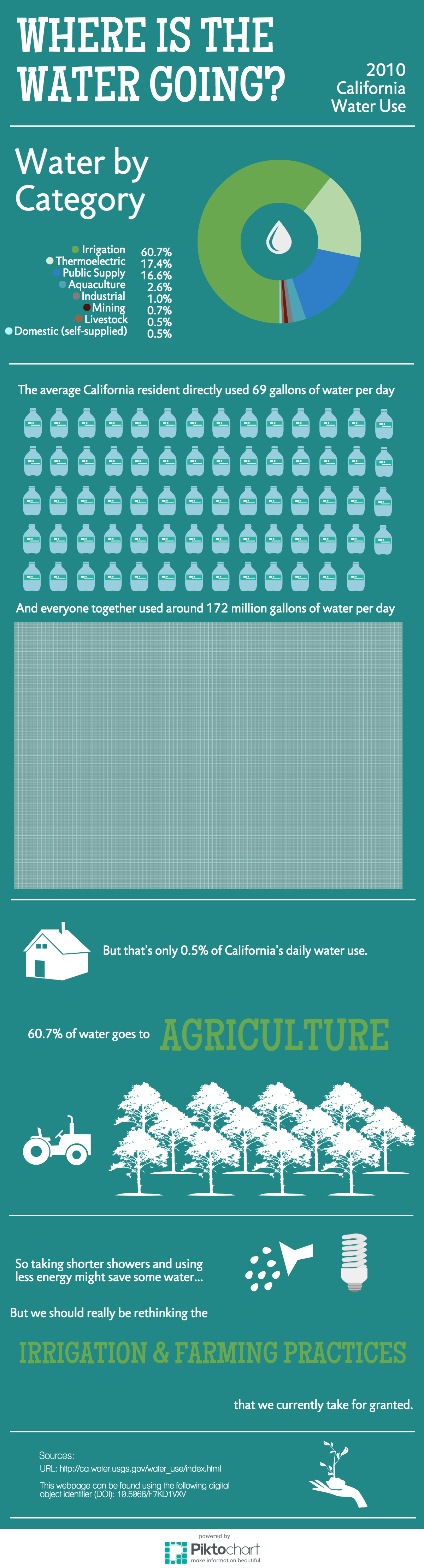

When we talked to them about lifestyle politics, most people thought that personal actions like shorter showers could have an impact on water use — “I believe that shorter showers could save water… but I’m not sure how short to take” and “Shorter showers would save water in theory, right? But I don’t do it.” After talking and reading the scroller narrative, they thought it was interesting how a lot of public policies focus on low flow toilets and showerheads when really they don’t make that much of a difference.

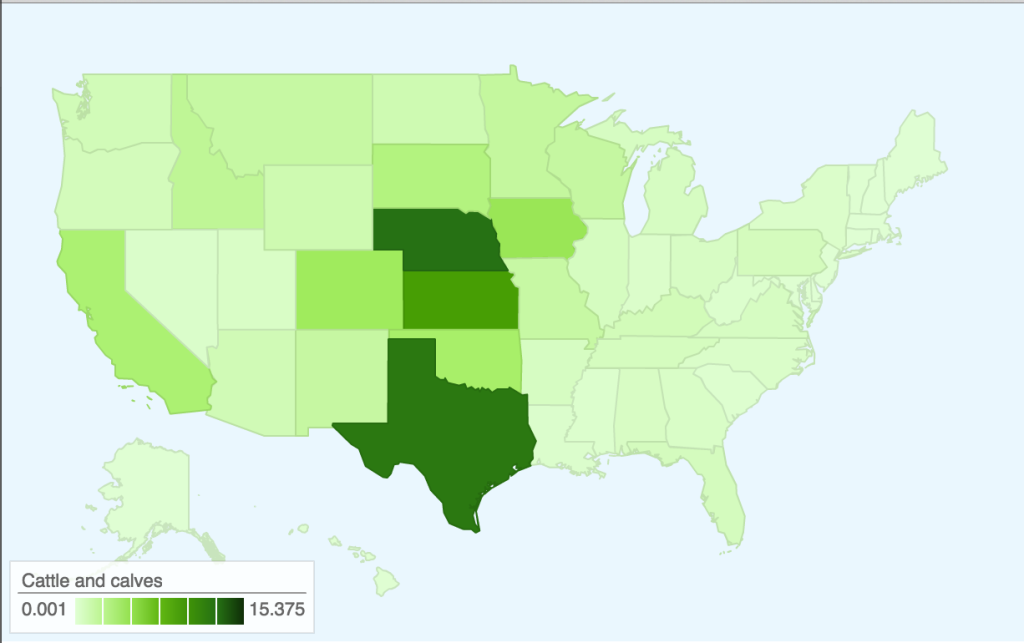

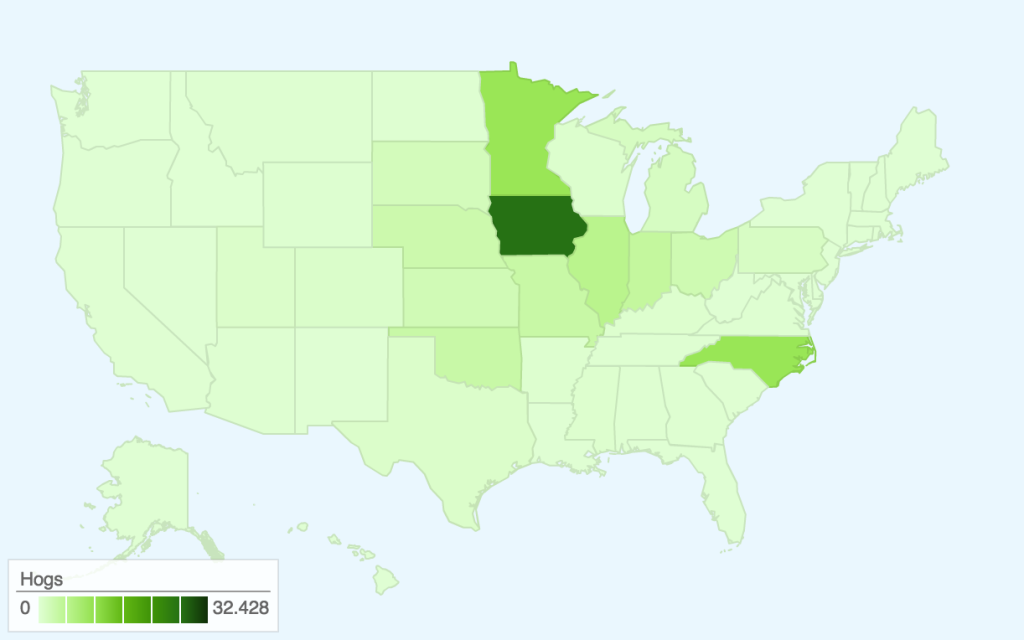

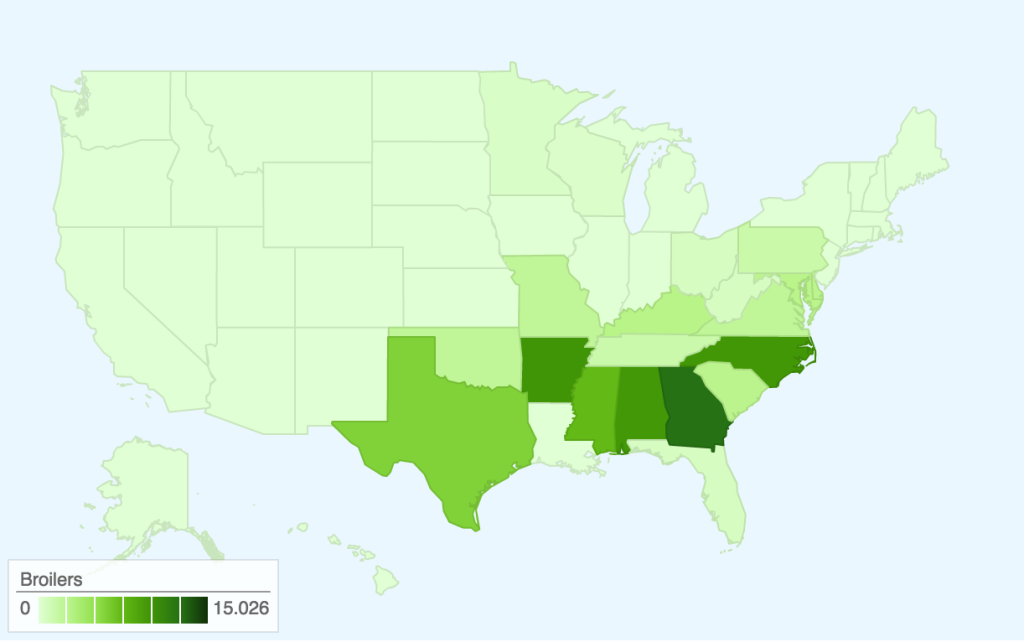

All but one of them were semi-regular meat eaters (the one was pescatarian on personal/ethical grounds), and were either surprised by the fact that food is a majority of your daily water use or anticipated it — “It makes sense that food contributes so much to your daily water use… because agriculture,” “Don’t almonds take a lot of water? I didn’t buy them last week on principle,” “Food? Really? cool.”

However, besides the one person that didn’t buy almonds at the grocery store recently, they wouldn’t feel motivated to change their diets because of their daily water use, or say that they might unintentionally be saving water — “I already go several meat-free days a week because I’m lazy and don’t want to cook it, so I probably wouldn’t make more changes.” And they weren’t sure if they would radically change their food habits if meat were more expensive either — “it’s hard to imagine how my shopping trips would change, and I always buy groceries on a budget… I’d probably just buy some meat anyway and get less of something else.”

Not many people knew about the impact of government subsidies on making the cost of food disproportionate to the water cost of that food, especially when it comes to livestock — “it’s weird to think about the relationship between water, government funding, and livestock… it’s not an immediate connection I would make.”

But, overall, they did not feel like the visualization motivated them to make any sort of lifestyle change or get involved with activism. It helped some of them solidify the idea that lifestyle changes are a personal decision and are mostly symbolic (whether they’re ethical, religious, political, etc. beliefs) rather than impactful — which made some people feel “kind of hopeless… because we can’t really do anything personally to affect industrial agriculture [or capitalism!] without joining a huge movement.”

It encouraged some people to learn a bit more about drought — “maybe I’ll pay more attention to drought in the news.” But nobody would really want to get involved with water conservation/awareness activism — “I would get involved if it was easy to get involved,” “I have no desire to get involved,” “No, I don’t want to be more involved.”

Overall, it seems like our scrolling visualization helped people learn a couple new things about drought, lifestyle politics, government farm subsidies, and the relationship between food and water. It worked as an educational tool, but didn’t necessarily motivate people to enact change in the world, which is probably okay given the scope of the project.