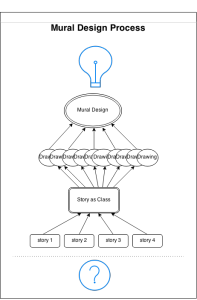

I found the mural design process of our class very different from my previous design processes. First, let me briefly lay out our mural design process:

- Introduction to the organization (Food For Free) through the voice of the director

- Group discussion to find a story based on the follow criteria:

- importance: impact on the audience

- relevance: relevant to the organization and to us

- accuracy: how well-supported by data

- Summarize the story into a sentence. Add why we want to tell this story -> Sticky!

- Gather as a class and share each group’s sticky note

- As a class, write the core sentence of the story we want to tell through the mural

- Word Web activities with three seed words: security, impact, waste

- Starting with each seed word, branch out with whatever words that come into mind

- Collective drawing

- Each person starts drawing and passes around to next person so that everyone contributes to each other’s drawing in continuation

- Put on the board and share

- Decide on the mural design as a class

- Find repeated imageries/themes from the collective drawings

- Incorporate them into one design

Some reflections on this design process helped me to compare it to one of my previous projects. During the cold and snowy winter of 2014, I and three other MIT students worked to design an interactive dashboard that analyzes Twitter and Facebook activities of non-profit organizations. Briefly speaking, below is the procedure we followed:

- Discussion on the basic frame of the dashboard: contents, functions, purposes

- Analyze data

- Each team member analyzes same data but work for different goals

- Push each findings and codes on Github which allow other members to quickly reuse or build upon the code

- Write a report on the analysis

- Two members are in charge of the write-up

- Build interactive dashboard based on the findings

- Two members are in charge of hosting the byproduct online

This process is similar to the mural design process in that it had modularity and involved group efforts within each module. First, the modularity arose from the step-by-step procedures and several milestones we established as checkpoints: the goal of the project was defined first, and the process was broken down into three smaller steps/milestones. The difference arises in the way tasks were distributed between the members. Instead of a group of individuals working together to finish a small module, each person was in charge of a designated task at each step. Each task was discussed after the corresponding milestone was reached, and each code was ready to be reused by other members if needed. This combination of distribution and code-sharing helped to maintain communication between members while enforcing the modularity in the process. It was however harder to understand other members’ tasks and thought-process, which required that everyone became an expert in his/her given task. In comparison, the mural design process did not rely heavily on any particular individual because each module was done in a group. I definitely felt that the mural process better captured the ideas common and prevalent in our class; it somehow felt more democratic.

The two design processes discussed above share similarities in its step-by-step approach and distributed workload. However, they are different in the way each step is finished and each task was incorporated into the final design; the design mural process had one more filtering layer in which the entire class decided what to include from each group’s work. Both of the processes have pros and cons, and it is important to know which path to take according to the goal and circumstances of the work.